FDM Startup Feb 25, 2018

From 2012 to 2014, I cofounded and led engineering at a startup that produced an FDM 3D printer, one of the first on the prosumer market to achieve reliability and professional print quality, and to feature soluble support. Our original website, preserved for posterity, can be seen here. (Regarding the name: it seemed fantastic in 2012: short, and relevant to making things. We had no idea of the world events that would soon unfold.)

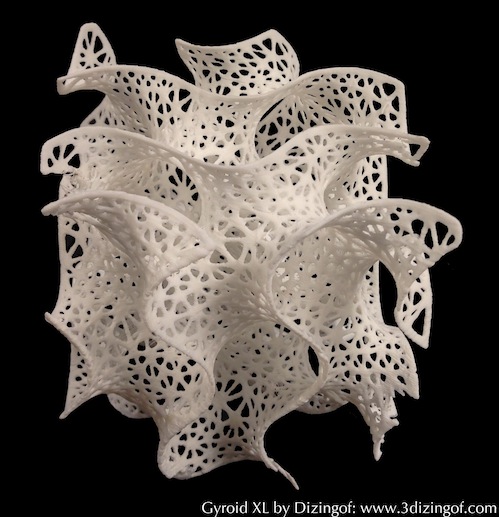

Though it has become a poster child for undeserved hype, 3D printing looked in 2012 like a technology with fundamentally transformative potential. We believed (and still do), that additive manufacturing would play a major role in the world economy by making it possible to produce highly complex physical objects very cheaply. To realize this, either the cost of the high-quality commercial machines (e.g. Stratasys) would have to dramatically decrease, or the quality of the hobbyist machines (e.g. MakerBot) would have to dramatically increase. The former seemed unlikely, but we didn’t perceive a reason for the latter not to happen quickly.

We decided to begin at the consumer end, where the 3D printers of the day were notoriously unreliable—prints required constant babysitting and still failed more often than not. If they did succeed, they weren’t good for much of anything: resolution was low, only one material could be used at a time, and unsupported features were impossible. The printers of 2012 were toys and little more.

Most great pieces of tech started life as toys, though, and we decided to start playing. With a college friend (who became my cofounder) I build a RepRap—a MendelMax 1.5—which we ended up modifying heavily to get it to work. After a few months of tinkering and improving, it was clear to us that a significant improvement was possible on the state of the art.

The new design we set out to create, first and foremost, had to be useful as something more than a toy. This meant several things:

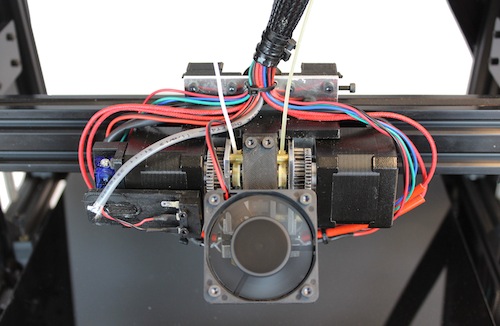

Beginning with what we’d learned on our MendelMax test bed, we created a clean-slate design, the Isis One. We achieved good layer stacking by rigorously testing over a dozen different linear systems. We designed a rigid but adjustable heated borosilicate print bed, and implemented an automatic bed level compensation algorithm called dynamic bed leveling. A similar system is now used on most high-end consumer FDM machines, but ours was the first in the space. Finally, to bring soluble support online, we created a robust dual-extruder printhead, advancing the state of the art of both the filament drive and hotend portions.

Though the startup ultimately failed in manufacturing, the Isis One was a radical improvement in the usefulness of consumer FDM. Its design is open source; files can be found here. The more detailed story of its creation is told below: